It’s the most durable biological material you’ve never heard of: sporopollenin.

This naturally occurring polymer coats and protects individual grains of plant pollen, and it’s been found in 500 million-year-old sediments. (It’s not the stuff that causes allergies – those are proteins within the pollen itself, not the coating.)

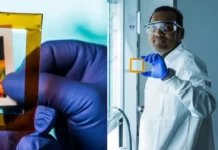

Synthetic biologists at Colorado State University are attempting to manufacture sporopollenin in the lab using plants and to control its properties using gene parts designed for specific functions, known as genetic circuits. Their goal is to produce coatings that could one day protect ships, bridges and other infrastructure that crack as they age.

DARPA funding

They’ll get there thanks to a $1.7 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), part of the U.S. Department of Defense. DARPA is known for funding extremely difficult, high-risk, high-reward science. The award to CSU researchers may be eligible for another $2.1 million for two additional years, if their methods prove successful.

The project’s lead is Mauricio Antunes, special assistant professor of biology at Colorado State University. Antunes will work closely with co-collaborator June Medford, professor of biology. Antunes and Medford have worked together in plant synthetic biology for 14 years. Joining in the effort from Medford’s lab will be Kevin Morey, special assistant professor of biology.

The other key player in the partnership is Matthew Kipper, associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering and School of Biomedical Engineering. A materials scientist, Kipper will help the team characterize the structure and function of the sporopollenin-like materials they make using specialized, high-resolution microscopy and spectroscopy.

Read more: Synthetic biologists engineer world’s strongest biomaterial

thumbnail courtesy of colostate.edu