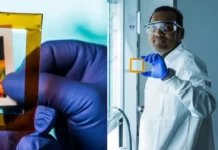

Stanford medical student Kevin Cyr is part of a team of researchers using 3D printing to build custom cardiac surgical devices.

Second-year medical student Kevin Cyr is part of a team of Stanford researchers investigating new ways to survey electricity in the heart. The research has led to the development of cardiac surgical devices that could one day help patients who suffer from a common heart ailment.

“I’m using 3D-printed tools to design cardiac-mapping catheters, devices used by surgeons to map the electrical activity of the heart and find disturbances,” says Cyr.

The research began a few years ago under the direction of Anson Lee, assistant professor of cardiothoracic surgery. Cyr, whose background is in bioengineering, joined the team last year as a student interested in developing new medical technologies that can transition from research to clinical practice.

Their investigation is focused on atrial fibrillation, or AFib, a heart disorder characterized by irregular and often rapid heartbeats that disrupt the flow of blood from the heart to the rest of the body. It is the most common rhythm disorder, which affects more than 6 million Americans and is responsible for over 750,000 hospitalizations every year. While some AFib patients have few, if any, problems, others suffer serious complications requiring surgery or medications.

Cyr says that finding and understanding rhythm disturbances in patients has been challenging because of the one-size-fits-all nature of existing medical devices, which use electrodes that contact the surface of the heart to measure electrical activity. So the researchers created devices that are customized to each patient, conforming to the unique contours and divots of the individual’s heart.

To do this, patients undergo an MRI or CT scan that records an image file of their heart, which is then fed into a 3D printer. Cyr says that using the scan, “we can replicate that natural geometry and anatomy specific to that patient” and apply it to the device.

Read more: Stanford University Creates Better Cardiac Catheter Devices with 3D Printing

thumbnail courtesy of news.stanford.edu