The technology will revolutionize manufacturing, but how? United Technologies, GE and Honeywell are taking different approaches.

Like the cotton gin and the modern assembly line, 3D printing is the kind of breakthrough advancement that holds the promise to revolutionize manufacturing. The technology lets companies input designs into a printer the size of a small garden shed and have it spit out fully formed, usable products or parts – often at a savings of time, manpower and money.

This potential isn’t lost on industrial giants like General Electric Co., Honeywell International Inc., and United Technologies Corp.: if you can make a part cheaper, faster or better, that’s worth something. So all three companies are investing in the technology and using it to rethink the way they run their businesses. But they’re doing so in different and interesting ways.

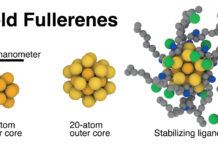

Traditionally, metal parts are carved or molded out of raw materials like aluminum or steel. The 3D printers used by industrial companies build components in a different way, by adding layers of metal powders on top of each other; that process is what’s earned the technology the name “additive manufacturing.” It’s a natural fit for the aerospace industry because printed parts are typically lighter, and lighter planes are more fuel-efficient – so that’s where you see these companies making the biggest strides.

GE, which spent nearly $1 billion to acquire two 3D printer businesses in 2016, is taking a bottom-up approach and looks at the technology as a creative medium that can help it improve the design of jet engines. Honeywell is content to buy 3D printers from third parties including GE and for now, sees this technology as a tool that it can embed in its supply chain to increase efficiency. United Technologies is taking a science-heavy tack. They’re all angling for a piece of a global additive manufacturing industry that generated about $10 billion in revenue last year, according to Wohlers Associates Inc.’s annual report on the industry. That’s not a huge number, but this is just the early stages, and it will only grow from here. The figure also doesn’t take into account the money spent on internal investments and the sales enabled by integrating 3D printing in the manufacturing process, which is harder to quantify but likely in the billions.

Honeywell has a football-field-sized complex filled with 3D printing machines at its aerospace headquarters in Phoenix, Arizona. They have names: there’s “Pebbles” and “Bamm Bamm”; “Luke Skywalker” operates out of a building separate from “Princess Leia”. 1 That will likely come as a surprise to investors and analysts. The company has rarely if ever, talked publicly about its 3D printing operations to Wall Street and the one link I could find for an additive manufacturing page on Honeywell’s website appears to have been disabled. Yet its methodical approach to the technology has given it an early lead by one measure: It has more parts qualified by the Federal Aviation Administration to fly on a plane than its rivals. So far, Honeywell has obtained approval for 18 parts including an engine surge duct and it expects to have an additional 14 cleared by the end of the month. All in, the company thinks it can get the FAA’s blessing to swap printers for traditional manufacturing processes on 250 aerospace parts by the end of this year.

Read more: Your Next Flight Is Brought to You by 3D Printing

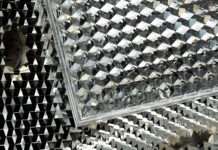

Image courtesy of General Electric

Related Links: