Designed to Adapt: Living materials are the future of sustainable building: Working together across disciplines, researchers from Penn State and the University of Freiburg are applying materials that adapt, respond to the environment, self-power, and regenerate to meet the challenges of adaptive architecture.

The coming decades present a host of challenges for our built environments: a rising global population combined with increasing urbanization; crumbling infrastructure and dwindling resources to rebuild it; and the growing pressures of a changing climate, to name a few.

To become more livable for more people, cities themselves will need to become smarter, with buildings, bridges and infrastructure that are no longer static but dynamic, able to adapt and respond to what’s going on around them. If not exactly alive, these structures will need to be life-like, in important ways. And for that, they’ll need to incorporate living materials.

“Engineers and scientists have worked for hundreds of years with so-called smart materials,” says Zoubeida Ounaies. “Piezoelectricity was discovered in the 1880s.” Smart materials can sense and respond to their environment, she explains, “but they always need an external control system or source of power. Living materials that adapt, respond to the environment, self-power, and regenerate—in the way that materials in nature do—are the next logical step.”

Ounaies, a professor of mechanical engineering at Penn State, is director of the Convergence Center for Living Multifunctional Material Systems, a research partnership between Penn State and the University of Freiburg in Germany. Known as LiMC2, the center is one of only a handful in the world focused on this emerging field.

A new paradigm: Engineered materials inspired by nature

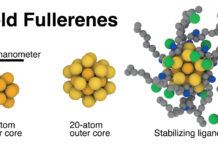

Designed to Adapt: Living materials are the future of sustainable building: Living materials, Ounaies explains, are engineered materials that are inspired by nature. Sometimes they even incorporate biological elements. Their dynamic properties, at any rate, enable them to adapt to changes in their environment, responding to external stimuli. They may change shape, heal themselves, even make simple decisions.

Ounaies’s counterpart at Freiburg is Jurgen Ruhe, director of the Cluster of Excellence in Living, Adaptive and Energy-autonomous Materials Systems (livMatS). At a webinar last summer Ruhe put it this way: “If we look at the materials of today, one of the very key features is that materials have properties which do not vary in time. But if we turn our view to nature, nothing is really constant. For living systems, adaptivity is the key to survival. The goal of our livMatS cluster is to generate materials systems which can adapt to changes in the environment based on sensory input and then improve over their lifetime.”

Importantly, Ounaies says, living materials are multifunctional. They don’t just provide strength or elasticity or hardness, they reduce environmental impacts and promote health; they monitor their own status, and when used up they can be recycled or reabsorbed. They harvest energy from their surroundings, store it, and use it for what they need. They do these things, ideally, while self-powering and without external sensors or motors.

Above all, perhaps, engineered living materials aim to be sustainable. “The concept requires us to look at the whole life cycle,” Ounaies says. “To think about the starting material, the extraction and manufacturing processes, the waste generated, the energy required.” The design must account for all. Thus, unlike many smart materials, living materials don’t put a harmful load on the environment.

Designed to Adapt: Living materials are the future of sustainable building: “If you think about it,” she says, “adaptive behaviors happen in nature all the time. Maybe not in a material form, but certainly in systems. There are plant systems that do this. There are animals that do this. ” Nature does the original design work. “For example, if one investigates the hierarchical pattern of a mollusk shell or the intricate structure of bird wings, one is inspired to apply them to human made structures in ways that integrate multiple functionalities.”

Thomas Speck has been fascinated by biomimetics for 30 years. Trained as a biophysicist, Speck is now professor of botany at the University of Freiburg. He studies the functional morphology of plants—the relationship between structure and function—and how these “biological role models” might be applied to the world of technology. As director of the University’s Botanic Garden, he has over 6,000 species from which to find his inspiration.

Plants, says Speck, have important lessons to offer. “First, they are mobile, although their movement is often hidden from us,” he explains. “A lot of plant movements are very aesthetic—think of a flower opening. We want to transport this aesthetics into our architectural solutions.”

Designed to Adapt: Living materials are the future of sustainable building: Full article

Material that Responds to Heat or Cold Without a Power Source