Force has Strong Impact on Metal Nanosheets: You have to look closely, but the hills are alive with the force of van der Waals.

Rice University scientists found that nature’s ubiquitous “weak” force is sufficient to indent rigid nanosheets, extending their potential for use in nanoscale optics or catalytic systems.

Changing the shape of nanoscale particles changes their electromagnetic properties, said Matt Jones, the Norman and Gene Hackerman Assistant Professor of Chemistry and an assistant professor of materials science and nanoengineering. That makes the phenomenon worth further study.

“People care about particle shape, because the shape changes its optical properties,” Jones said. “This is a totally novel way of changing the shape of a particle.”

Jones and graduate student Sarah Rehn led the study in the American Chemical Society’s Nano Letters.

Van der Waals is a weak force that allows neutral molecules to attract one another through randomly fluctuating dipoles, depending on distance. Though small, its effects can be seen in the macro world, like when geckos walk up walls.

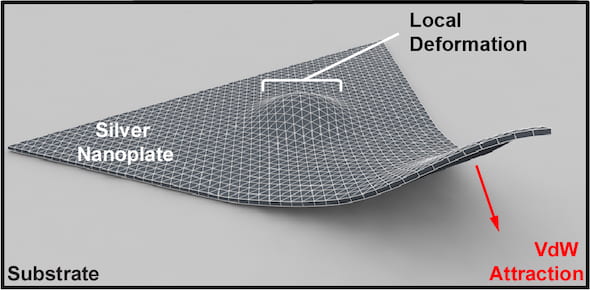

“Van der Waals forces are everywhere and, essentially, at the nanoscale everything is sticky,” Jones said. “When you put a large, flat particle on a large, flat surface, there’s a lot of contact, and it’s enough to permanently deform a particle that’s really thin and flexible.”

In the new study, the Rice team decided to see if the force could be used to manipulate 8-nanometer-thick sheets of ductile silver. After a mathematical model showed them it was possible, they placed 15-nanometer-wide iron oxide nanospheres on a surface and sprinkled prism-shaped nanosheets over them.

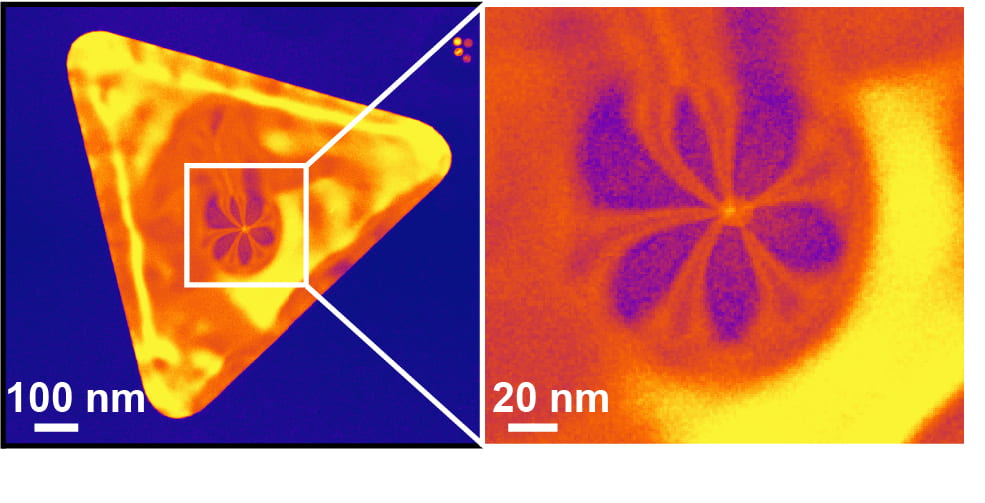

Without applying any other force, they saw through a transmission electron microscope that the nanosheets acquired permanent bumps where none existed before, right on top of the spheres. As measured, the distortions were about 10 times larger than the width of the spheres.

The hills weren’t very high, but simulations confirmed that van der Waals attraction between the sheet and the substrate surrounding the spheres was sufficient to influence the plasticity of the silver’s crystalline atomic lattice. They also showed that the same effect would occur in silicon dioxide and cadmium selenide nanosheets, and perhaps other compounds.

“We were trying to make really thin, large silver nanoplates and when we started taking images, we saw these strange, six-fold strain patterns, like flowers,” said Jones, who earned a multiyear Packard Fellowship in 2018 to develop advanced microscopy techniques.

“It didn’t make any sense, but we eventually figured out that it was a little ball of gunk that the plate was draped over, creating the strain,” he said. “We didn’t think anyone had investigated that, so we decided to have a look.

“What it comes down to is that when you make a particle really thin, it becomes really flexible, even if it’s a rigid metal,” Jones said.

In further experiments, the researchers saw nanospheres could be used to control the shape of the deformation, from single ridges when two spheres are close, to saddle shapes or isolated bumps when the spheres are farther apart.

They determined that sheets less than about 10 nanometers thick and with aspect ratios of about 100 are most amenable to deformation.

Force has Strong Impact on Metal Nanosheets: The researchers noted their technique creates “a new class of curvilinear structures based on substrate topography” that “would be difficult to generate lithographically.” That opens new possibilities for electromagnetic devices that are especially relevant to nanophotonic research.

Straining the silver lattice also turns the inert metal into a possible catalyst by creating defects where chemical reactions can happen.

“This gets exciting because now, most people make these kinds of metamaterials through lithography,” Jones said. “That’s a really powerful tool, but once you’ve used that to pattern your metal, you can never change it.

“Now we have the option, perhaps someday, to build a material that has one set of properties and then change it by deforming it,” he said. “Because the forces required to do so are so small, we hope to find a way to toggle between the two.”

Co-authors of the paper are graduate student Theodor Gerrard-Anderson, postdoctoral researchers Liang Qiao and Qing Zhu, and Geoff Wehmeyer, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering.

The Robert A. Welch Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the National Science Foundation supported the research.

Force has Strong Impact on Metal Nanosheets: Original Article

Technique Uses Silver Nanowires to Create Flexible, Stretchable Nanowire Circuits

Graphene-based ink may lead to printable energy storage devices